thoughts on eye movement

Visual perception research has produced many illusions. Stare at a waterfall for a minute, then look away and the whole world appears in motion, traveling upwards (Addams 1834). Given proper lighting, black paper can appear white, but placing a white piece of paper nearby colors the first dark gray (Gelb 1929; as cited by Cataliotti and Gilchrist 1995). Inspecting two sets of black lines – horizontal lines that obscure a solid red field like a picket fence, along with vertical lines that obscure a solid green field – causes the black lines alone to induce a perception of color, an illusory shading that can last for days (McCollough 1965). Such illusions reveal the intricacies of visual perception, kludges and all1. The pizzazz of the illusions affords visual perception a kind of scientific rigor; the effects are obviously real and reproducible, so to satisfyingly explain how visual perception works so well also requires explaining how atypical visual environments can so often dupe vision.

However, research on visual perception inevitably strays from fascinating and easily demonstrable illusions. Of course, even without the glamour of classic visual illusions an effect can still be a reliable and valid object of research. But as the effect becomes more subtle, observing the effect requires increasingly complex analyses. Unfortunately, the most complex analyses, when misapplied, can also transmute noise into something that appears noteworthy2. So when a subtle effect relies entirely on a complex analysis, the effect becomes suspect. To highlight the obviousness of an effect, it can help to visualize and revisualize the data.

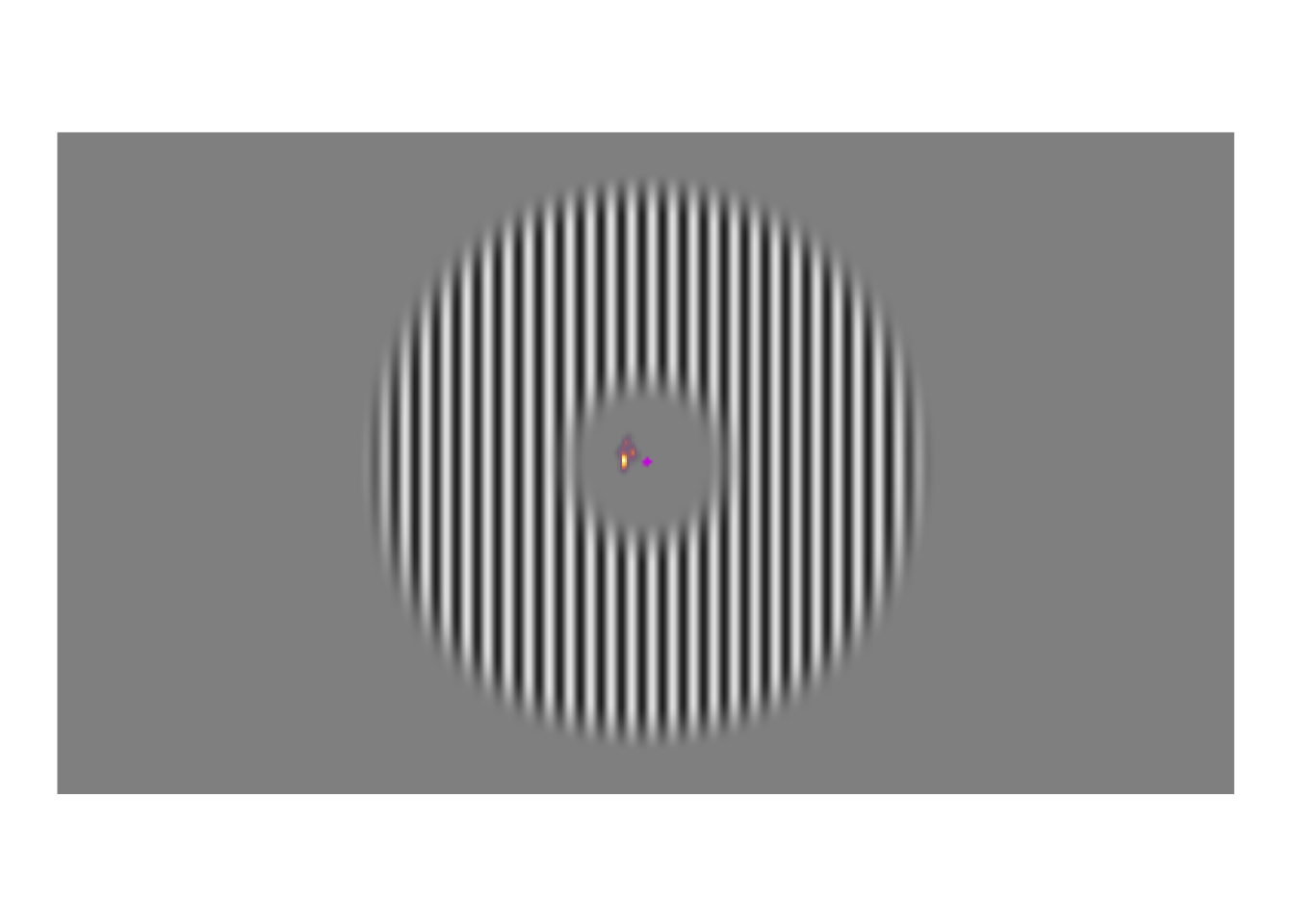

A few weeks ago, I posted about an effect that warrants revisualizing, the apparent stability of visual perception. I discussed this stability as one of the reasons that perception exhibits serial dependence (Fischer and Whitney 2014), which is the tendency of visual perception to be slightly erroneous, resembling not an accurate reproduction of the input it receives but a mixture of current input and input from the past. This dependence may occur during perception to refine the inherently erratic input provided by the retina. I attempt to demonstrate the need for refinement with Figures 1-3. Figure 1 shows a stimulus from an ongoing experiment. In the experiment, the participant was required to simply hold their gaze still. The figure is a heatmap, showing that this participant successfully fixated on a small region of the stimulus. However, the heatmap obscures how fixating on a “small” region implies ample movement. Figure 2 recapitulates, in real time, how the gaze wandered during fixation. But then Figure 2 obscures what that wandering means for the visual system; whenever the eye moves, the retina receives (and so must then output) a different image. With Figure 3, I attempt to visualize what these eye movements mean for the retinal image. In Figure 3, the movements of the gaze are transferred to the stimulus, revealing how the retina receives a twitching stimulus. The effect to explain here is why fixating at the dot in Figure 1 – given that the eyes move as shown in Figure 2 – does not elicit the jumpy movie depicted in Figure 3, but instead elicits the stable image of Figure 1.

Figure 1: Example stimulus, with heatmap of eye positions during one trial overlayed. Participants viewed such grating stimuli, each for five seconds. They were instructed to fixate on the central magenta dot. The blob to the left of the dot indicates where this participant looked during the trial; the brightest regions held their gaze for the most time.

Figure 2: Time course of fixations from Figure 1. The blue dot shows where the participant looked at each moment. Fixations were recorded at 1000 Hz, but this video has been downsampled to 10 Hz.

Figure 3: Approximate example of the retinal image from Figure 2. While the gaze travels throughout the visual environment, that environment is largely stable. Yet the travelling gaze constantly alters the image imprinted on the retina.

References

To personally experience the illusions mentioned here – and many others – explore Michael Bach’s website.↩︎

Full disclosure: I write this as someone who has written a paper on a novel development of an already obscure analysis, a development that I needed to support the claims in another paper. I am a kettle.↩︎