Staircases for Thresholds

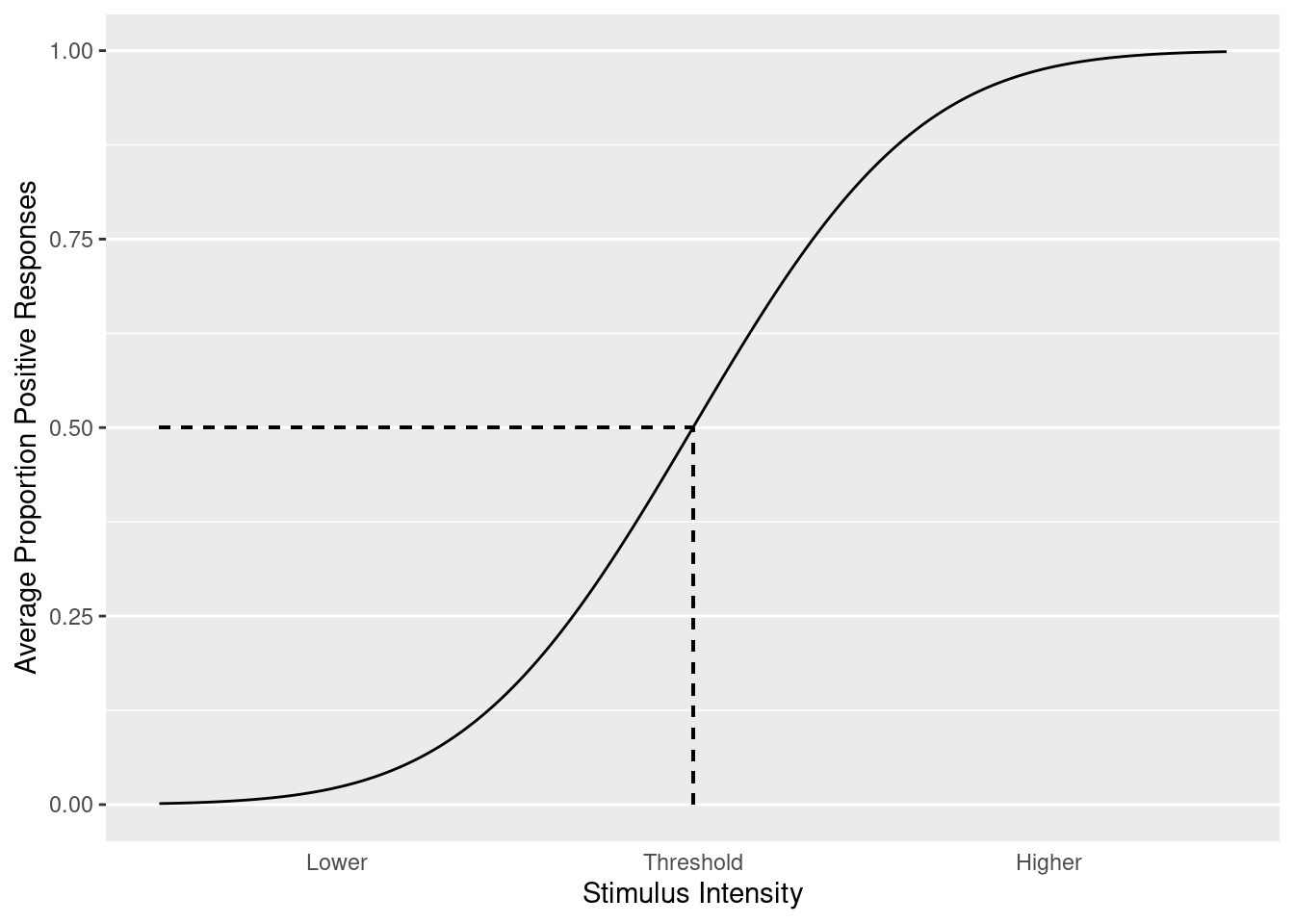

Performing any experiment on cognition requires deciding which stimuli to use. Some experiments require participants to make many errors, requiring the stimuli to be challenging. In other experiments, participants must respond accurately, requiring stimuli that are easy but not so easy that participants lose attention. Moreover, participants behave idiosyncratically, so to avoid wasting either the researchers’ or participants’ time the stimuli ought to be tailored to each participant. To decide which stimuli to use, researchers can rely on a psychometric function (Figure 1). These functions describe a relationship between the intensity of a stimulus and how a participant responds to that stimulus, when responses can be classified as either a positive or negative. Precisely what is meant by ‘intensity’ and ‘positive or negative’ depends on the experimental task, but they roughly correspond to the amount of stimulation on each trial and how difficult it is to notice that stimulation. In a task in which participants must detect a pure tone that is occasionally presented over white noise, the intensity could be the volume of the tone and participants’ responses are positive when they detect the tone. With a psychometric function, deciding on a stimulus translates to picking the proportion of trials that should receive positive responses – picking the desired difficulty – and then using the intensity that elicits that behavior. This replaces the task of picking stimuli with inferring participants’ psychometric functions.

Figure 1: A psychometric curve with threshold intensity. Psychometric curves relate the intensity of stimulation to the perception of stimulation, or the proportion positive responses. There are many parameterizations of these functions, but they are typically sigmoidal. The intensity at which, on average, half of responses are positive is often of interest. This intensity is called the threshold.

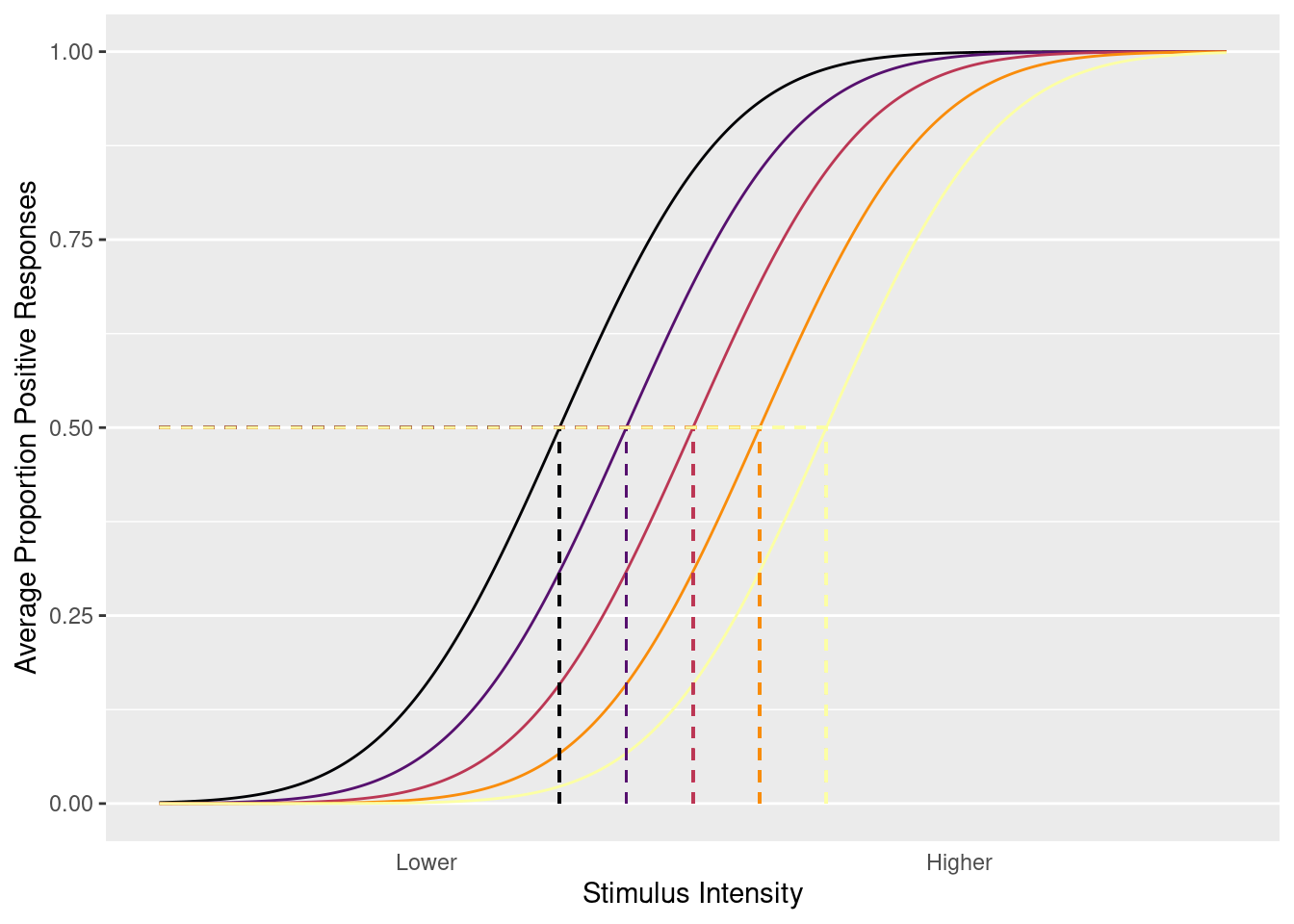

To infer psychometric functions, standard procedures exist, though these procedures have varied efficiency. In particular, when only a single stimulus intensity is required, it would be inefficient to estimate the entire function. Consider a researcher attempting to elicit half positive responses, behavior elicited by the so called threshold stimulus intensity. A simple procedure to infer the psychometric function involves presenting a wide range of stimulus intensities, fitting the function to the data, and using the estimated function to infer the threshold. Each datum increases the precision of the estimate, but some data will be more useful than others. Intensities close to the tails of the function will pin down the function at those tails, but functions with different thresholds can behave similarly in their tails (Figure 2). The threshold is most tightly constrained by responses to stimuli at the threshold (Levitt 1971). Therefore, an ideal procedure to estimate the threshold intensity would involve repeatedly presenting the threshold intensity. The ideal procedure is unfeasible, since if the threshold were known there would be no need for inference. But although the exact threshold intensity cannot be presented on every trial, certain procedures enable most trials to approximate the ideal.

Figure 2: Psychometric functions with different thresholds. Although behavior at the tails of these functions are similar, they have different thresholds.

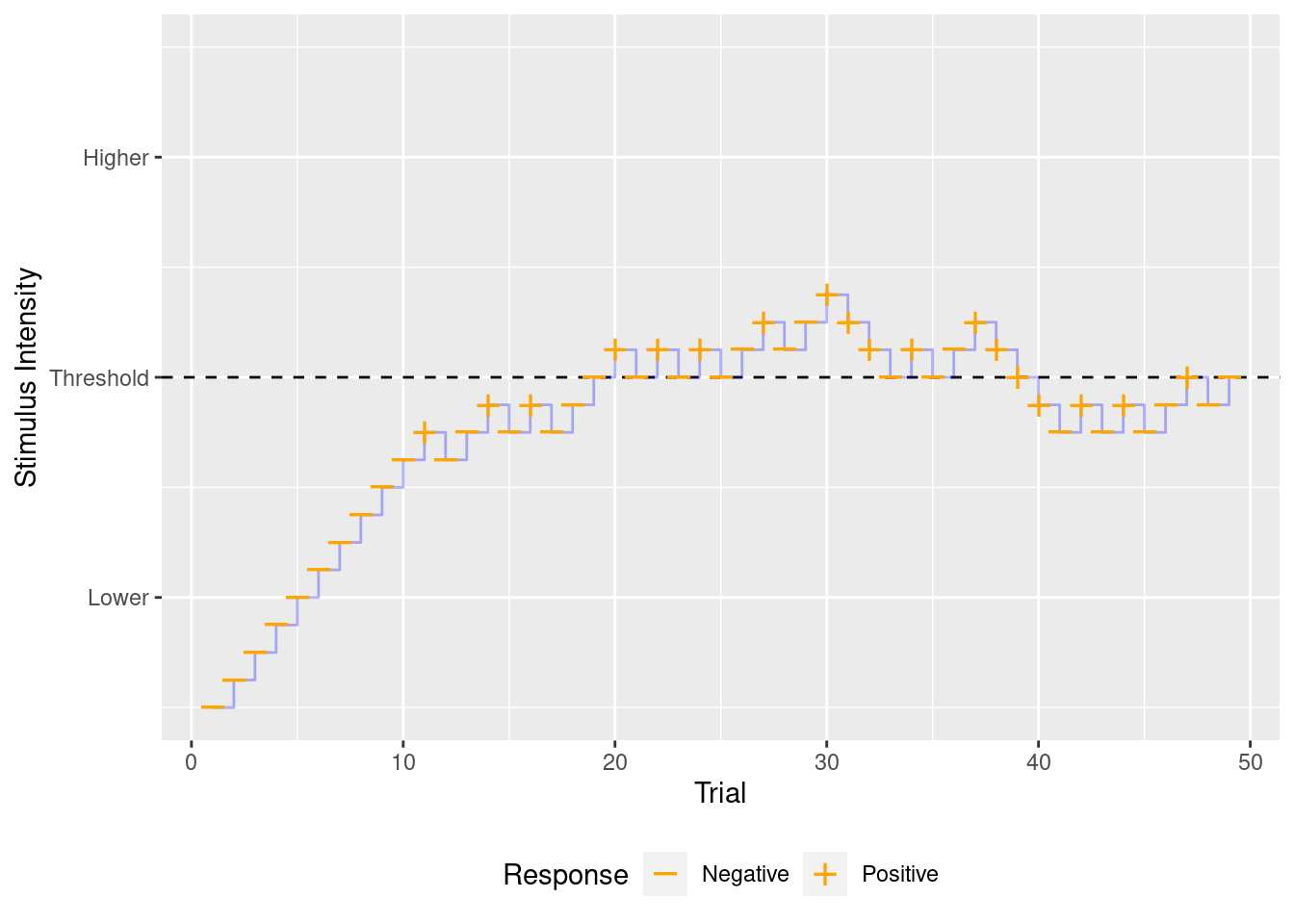

One type of procedure that locates the threshold intensity, both simply and efficiently, is called a staircase. A staircase procedure changes the stimulus intensity on every trial based on how participants respond. A staircase that locates the threshold increases stimulus intensity after a participant makes a negative response and decreases the intensity after a participant responds positively. Even when the first stimulus has an intensity far from the threshold (Figure 3), the staircase brings the intensity to the threshold, a convergence that is ensured by the psychometric function. For example, when intensity is lower than the threshold, a participant tends to make negative responses. After a negative response, the contrast is increased. With an increased contrast, the participant will be more likely to make a positive response. If the intensity is still lower then then threshold, the participant will likely provide another negative response, causing the intensity increase further. After enough trials with intensity too low, the intensity will be pushed towards the threshold. If the intensity strays from the threshold, the same dynamics push the threshold back to threshold. The staircase forces the intensity to remain close to the threshold.

Figure 3: Example sequence of trials in which stimulus intensity is controlled by a staircase procedure. After each negative response, the intensity increases, and after each positive response the intensity decreases. Although the initial intensity was much lower than the threshold, the staircase brings the intensity close to threshold and then keeps it there.