Staircases for Thresholds, Part 2

In last week’s post, I discussed how some experiments in cognitive psychology require researchers to pick a differently intense stimulus for each participant. In particular, I discussed a procedure for picking an intensity that elicits positive responses on approximately half of trials, the staircase procedure. In the staircase procedure, the researcher increases the intensity after every positive response and decreases the intensity after every negative response. If the participant completes another set of trials in which the intensity is fixed to the average of the intensities that were used during the staircase, the participant will provide positive responses approximately half of the time. But a researcher may want participants to give positive responses with a different proportion. A different proportion of responses can be achieved by transforming the staircase (Levitt 1971).

The original staircase produced an intensity that elicited half positive responses by balancing the proportion of positive and negative responses. Intuitively, to elicit a higher proportion of positive responses, the transformed staircase must tilt this balance by converging on a more intense stimulus. Any staircase affects responses by changing the stimulus intensity as a function of how participants behave. The staircase that changes the intensity after every response is called a one-up, one-down staircase; one negative response causes the intensity to go up, one positive response causes the intensity to go down. A transformed staircase can make a positive response more likely by making intensity decreases less likely. The names of transformed staircases are analogous to the one-up, one-down label: a one-up, two-down staircase increases the stimulus after any negative response and decreases the intensity after two positive responses; a two-up, three-down staircase increases the intensity after two negative responses and only decreases the intensity after three positive responses; and so on. Altering when the staircase increments the intensity alters the intensity at which the staircase converges.

We can use algebra to calculate the proportion of positive responses elicited by the intensity converged on by a staircase. As an example, consider a staircase that increases the intensity after a single positive response but decreases the intensity after two negative responses, a one-up, two-down staircase. Since the one-up, two-down regime results in fewer decreases than the one-up, one-down staircase, we should expect that the proportion of positive responses will be higher than half. For the calculation, note that there are three possible sequences of responses that result in an intensity change. Two of these sequences cause an increase, either a single negative or a positive followed by a negative. For the algebra later, let \(p(x|i)\) be the probability of obtaining a positive response at stimulus intensity, \(i\). Our goal is to solve for this probability. Participants can only provide either positive or negative responses, so the probability of obtaining a negative response to that stimulus is \(1-p(x|i)\). The probability of increasing the stimulus intensity away from intensity \(i\), \(p(\text{up|i})\) is the sum of the probabilities for the two sequences:

\[ \begin{equation} p(\text{up|i}) = (1-p(x|i)) + p(x|i)(1-p(x|i)) \\ \tag{1} \end{equation} \]

There is only a single way in which the staircase decreases intensity: the participant must provide two positive responses in a row. The probability of the intensity decreasing away from \(i\), \(p(\text{down|i})\) is equal to the probability of two positive responses to that stimulus, or

\[ \begin{equation} p(\text{down|i}) = p(x|i)^2 \\ \tag{2} \end{equation} \]

Combining equations (1) and (2) will give a relationship that determines the proportion of positive responses participants will tend to provide under this staircase. To see how to combine these equations, remember that the one-up, one-down staircase converged on an intensity for which the proportion of positive and negative responses were equal. This equality occurred because at that intensity, the probability of an up and down step were equally likely. So, to determine at which intensity the one-up, two-down staircase converges, we must determine the probability of a positive response that will make an up and down step likely in the one-up, two-down staircase. That is, we set the right hand sides of equations (1) and (2) to be equal, and solve for \(p(x|i)\)1.

\[ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} p(x|i)(1-p(x|i)) + (1-p(x|i)) & = p(x|i)^2 \\ \implies p(x|i) - p(x|i)^2 + 1-p(x|i) & = p(x|i)^2 \\ \implies -2 p(x|i)^2 & = -1 \\ \implies p(x|i)& = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ & \approx 0.707 \end{aligned} \tag{3} \end{equation} \]

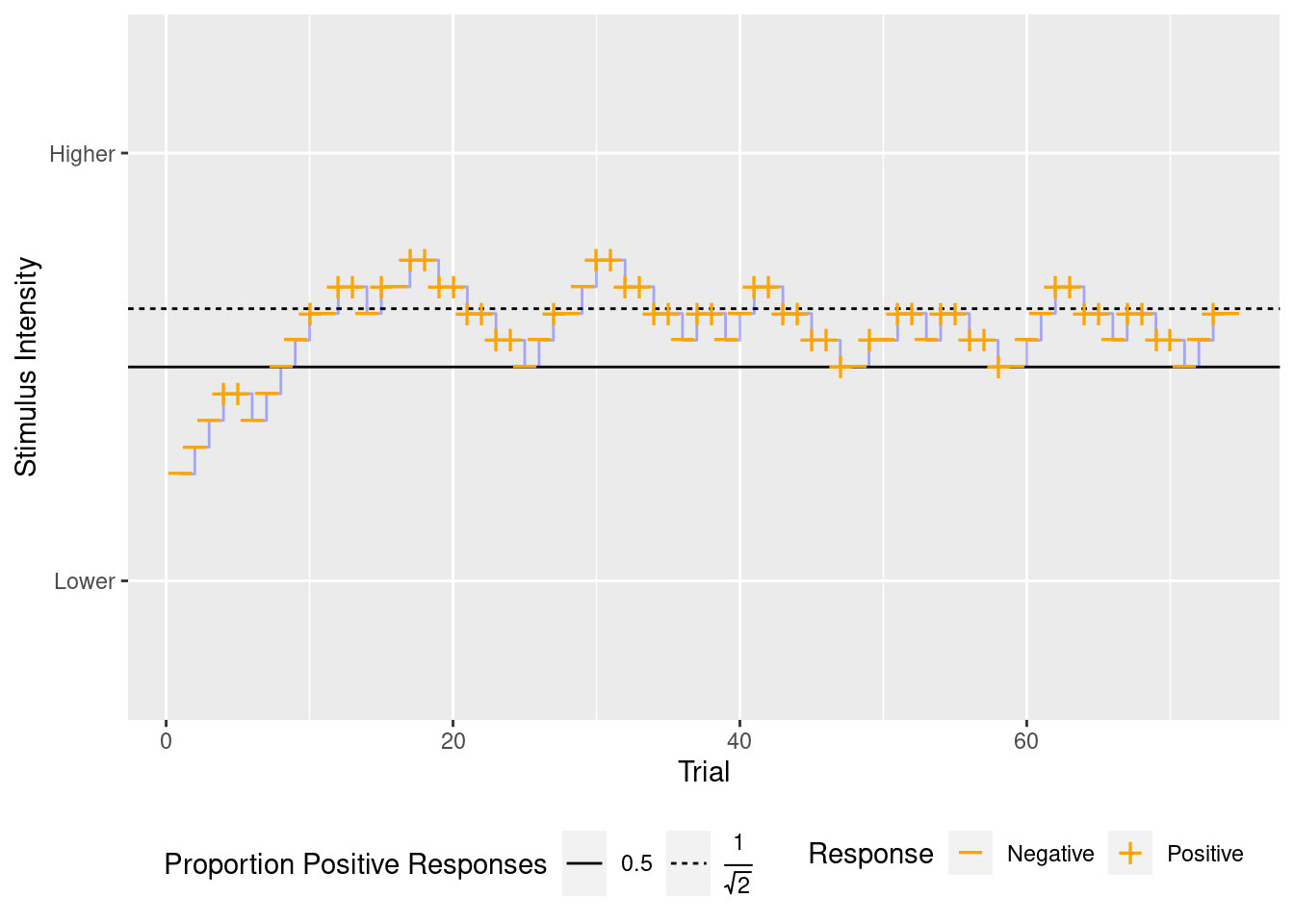

Equation (3) shows that a one-up, two-down staircase will converge on a stimulus intensity that elicits approximately 70% positive responses (Figure 1). As one way to see that this solution makes sense, relate this solution back to the probabilities of making either an up or down step. By equation (2), this solution implies that at this intensity, that an up step occurs with a 50% probability. As desired, any sequence that elicits a transition has an equal chance of being one that elicits either an up or down step.

The original staircase procedure capitalized on the idea that the stimulus intensity which elicits half positive responses can be estimated by starting from an arbitrary intensity, changing the intensity on every trial based on whether a participant responded positively or negatively, and then retroactively looking at which intensities were shown. The transformed staircase enables estimation of an intensity that elicits different behavior. Similar algebra to that outlined in this post can be used to determine the proportion of positive responses elicited by other staircases. Unfortunately, most proportions will not have an easy staircase regime. Moreover, complex staircases will only change the stimulus intensity infrequently, requiring more trials to estimate the converged upon intensity stably. However, the proportions reachable by simple staircase are often good enough; rare is the experiment that requires, not 70.7% but 73% positive responses. And the staircase procedure did not require any knowledge of the exact shape of the psychometric function, just that there was a psychometric function. The simplicity of the transformed staircase makes it an attractive way to pick an intensity.

Figure 1: A sequence of trials with stimulus intensity governed by a one-up, two-down staircase. With this staircase, the intensity increases after a single negative response but decreases only after two positive responses. After enough trials, the average of the stimulus intensities shown to participants will elicit approximately 70% positive responses (dashed line). The intensity resulting from a one-up, one-down staircase is shown for comparison (solid line).

References

The equation will have two solutions, but one of those solutions will be negative. A negative value is not an actual solution, because we are dealing with probabilities and so there is an additional constraint that \(0 \leq p(x|i) \leq 1\)↩︎