Modulations to tuning functions can bias evidence accumulation

Perceptual decisions can be deconstructed with evidence accumulation models. These models formalize expectations about how participants behave, when that behavior involves repeatedly sampling information towards until surpassing a necessary threshold of information. At a cognitive level, the different models instantiate the components differently, but at a neural level the models rely on common mechanisms. To accumulate evidence the models assume two distinct populations of neurons. One population responds to available information. This population can be thought of as a sensory population, such that each neuron in the population represents one of the available options. The second population listens to the first, transforming the sensory activity into evidence for each decision and accumulating the evidence through time. This second population can be called an integrating population. While the location of the sensory population depends on the information that needs to be represented, the location of the integrating population depends on the required behavior. If participants must make decisions about orientations, the sensory population might be striatal neurons tuned to different orientations. If participants make decisions with saccades, the integrating population might be in the frontal eye fields. Understanding how these two populations reveals different ways that decisions can be biased.

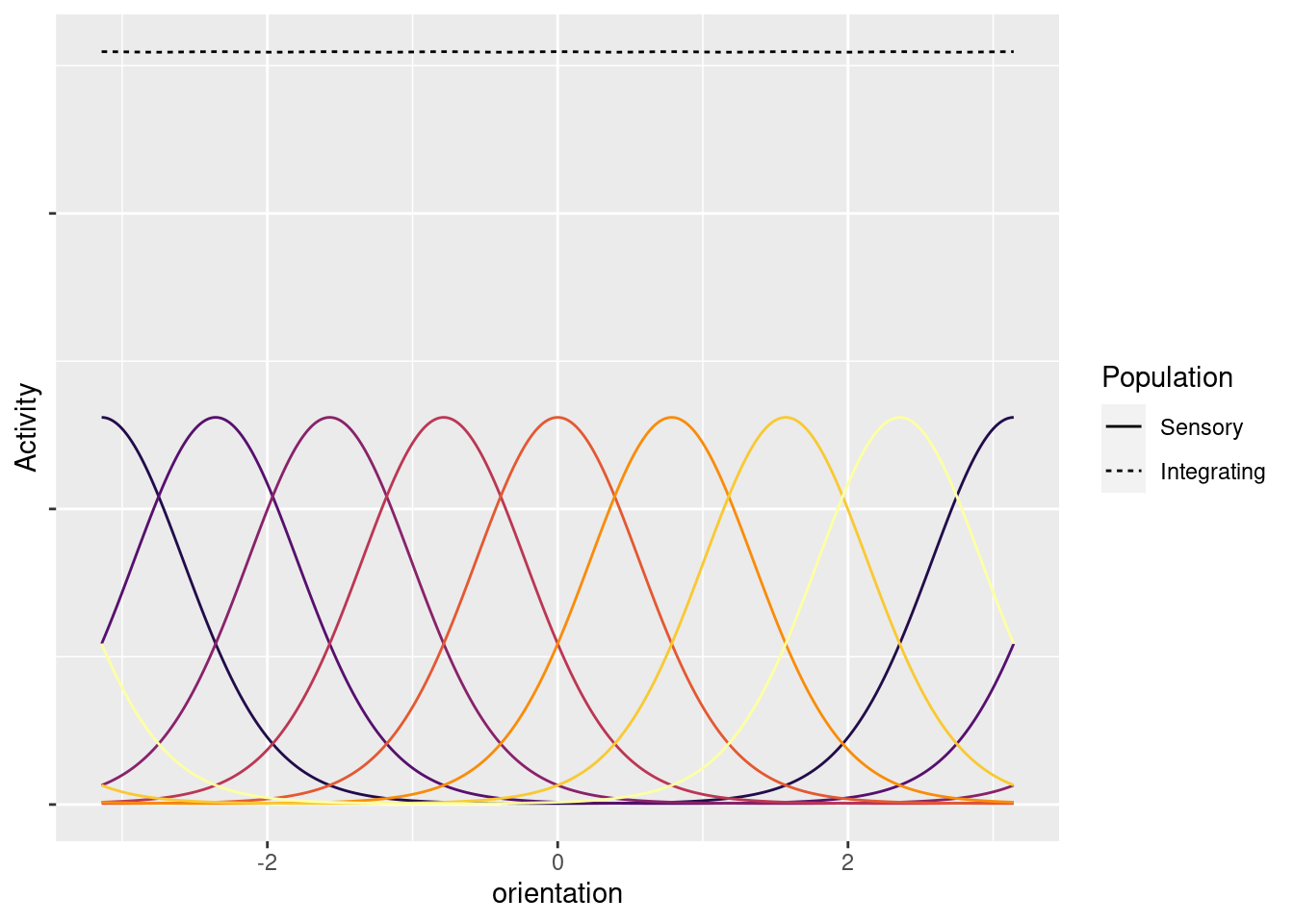

Figure 1: Sensory channels evenly represent orientations. The curves from the sensory population represent the average activity of each neuron to a given orientation. Although the curves show average activity, at any given moment the actual activity of each neuron may be higher or lower. The integrating curve reflects the average evidence that the integrating population will record. The flatness of the integrating curve reflects an unbiased representation. Only eight neurons from the sensory population are shown to avoid overcrowding.

For the integrating population to accumulate evidence, it must transform the activity of the sensory population into a meaningful signal. Figure 1 depicts that transformation when participants must report orientations. Each neuron in the sensory population responds most strongly to a specific orientation, but all of them are active whenever an orientation is present. The function describing how a sensory neuron respond to different orientations is called the neuron’s tuning function. The integrating population will respond according to some other function of that sensory activity. One simple integrating function associates each neuron with its preferred orientation; the integrating population then tallies evidence based on whichever neuron is most active. This function requires the sensory population to represent each orientation with at least one neuron. If there are enough sensory neurons, the integrating population will be able to accumulate evidence for each orientation without bias.

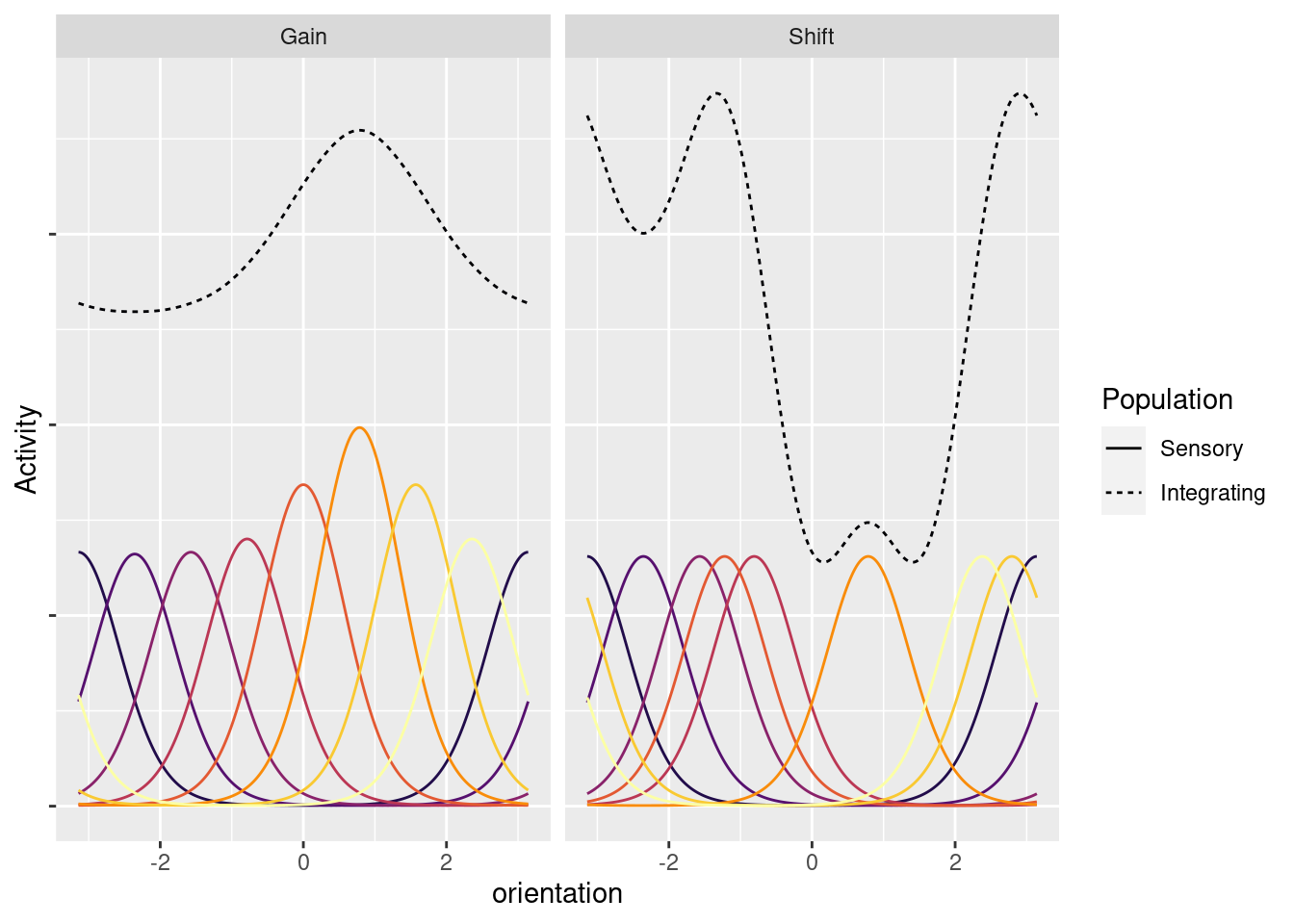

Figure 2: Modulations to activity of the sensory population will provide the integrating population a biased representation of the orientation. Unlike in Figure 1, the sensory population in both panels provides the integrating population with an uneven representation of orientation.

The tuning characteristics of sensory neurons are variable, and this variability causes biases to emerge in the evidence accumulation process (Figure 2). One common alteration is an increased gain, whereby the tuning function is multiplied by some value. When the gains of tuning functions are altered heterogeneously, a neuron may have a higher activity even when the orientation it is responsible for is not present. The neurons with the highest gain will bias the evidence gathered by the integrating population. Alternatively, tuning functions might shift, along with the orientation each neuron signals. The shift causes the sensory population to over-represent of some orientations and leave others underrepresented. These alterations can provide advantages in certain circumstances. For example, a heterogeneously increased gain will be useful when some orientations are known to be more likely than others, and a shift will be useful when different orientations require differently precise responses. But to accumulate evidence without bias, the sensory population must restore more uniform tuning.